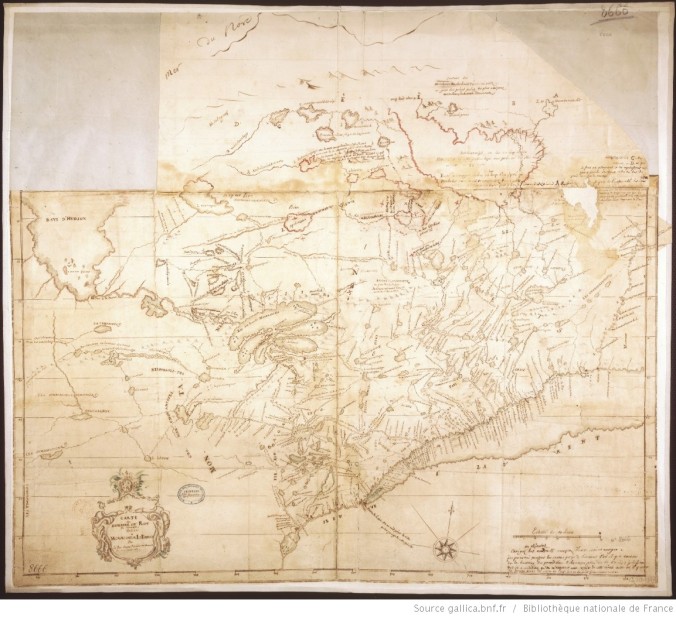

Map of Cree country made by the Jesuit Pierre-Michel Laure in 1731

As a child I couldn’t help but notice that my grandmother read a certain book every night before bed. You see, I loved books – dictionaries in particular – and would spend countless hours staring at their contents, much of which was cryptic to my young mind. So seeing my grandmother settling into bed one evening, I climbed up next to her in hopes that she would pull that book out and read.

She did, of course, but not before leafing through the pages to show me every little flower, leaf, and picture she’d inserted at random places to adorn this object that was obviously much more than a simple book to her. As she replaced the picture of an unknown relative, she finally began reading.

I sat next to her as she sounded out each arcane symbol in a reverential tone. It sounded so strange to my young ears. I had heard her speak Cree before – it was, after all, the only language I ever heard her speak. But this was different. It was Cree, but different.

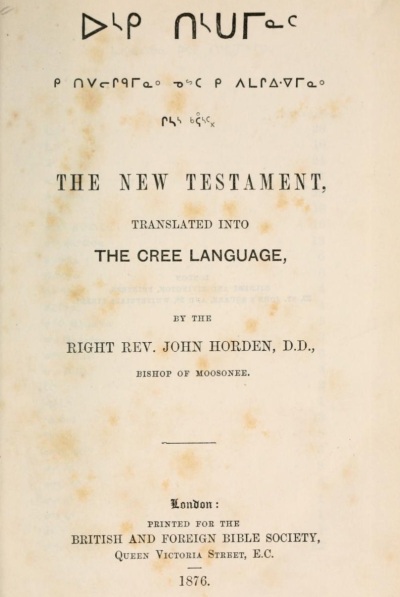

What exactly made it different would eventually become abundantly clear. She was reading the New Testament, a book translated into our language over 140 years ago by Bishop John Horden, whom my grandmother always called John Moosonee, and his unnamed associates. My grandmother sounded different as she read from the New Testament simply because it had been translated into a dialect spoken over 140 years ago at Moosonee – quite a stretch from the Waswanipi dialect she spoke in the 1980s.

The book my grandmother read on most nights before bed

Though there were obvious dialectal differences, I was never made to think that this was a different language. In fact, the thought that the written form could sound so different from our spoken language would plant a small seed in my young mind that later grew into an interest in the history of our language. It was only a matter of time before I realized I could combine this interest with my love of dictionaries into a lifelong obsession with lexicography.

Over the years this obsession has had me seek out any written source on our language I could find, but historical sources in particular have always captured my attention. There is something fascinating about the existence of Cree-language documents written centuries ago – and these aren’t only religious texts. While the latter are obviously quite numerous, word lists, dictionaries, grammars, letters, and maps also figure among the surviving examples of the historical language. While studying these priceless documents I cannot help but wonder who the Cree-speaking informants were. While the historical narrative has provided us with a few names and stories, like that of Pešâpanohkwew – the woman responsible for Pierre-Michel Laure’s 1726 dictionary – most have not been named, let alone thanked, for their assistance.

Regardless, many historical documents have survived and now have their own stories to tell. Their original religious and colonial purposes may have been insidious, but their continued existence will determine whether or not we chose to redeem them for our own purposes. I certainly have found much joy in studying their contents, almost religiously, reminiscent of my grandmother’s daily reading of the John Moosonee’s New Testament.

For those interested, historical documents relating to the Cree language can be viewed online at www.massinahigan.ca, a website conceptualized and built by John Bishop, Head of Toponymy for the Cree Nation Government and a good friend of mine.

Love it because I can relate to it

LikeLiked by 1 person

The http://www.massinahigan.ca/ link appears to be dead. I wonder if it can be revived!

LikeLike

I will inform the website owner! Thanks.

LikeLike