My latest post, Diving Duck, may have seemed a little left field to those who regularly visit my blog. Admittedly, the otherworldliness of some traditional stories is quite apparent when one is accustomed to fairytales such as The Little Red Riding Hood and Goldilocks. I refrained, however, from including any explanatory note and chose instead to let the story speak for itself. I did this with the intent of following the model set by my posts of European fairytales, stories which I translated into the Cree language to make them accessible to a larger public. In the same vein, I translated Diving Duck into the English language and plan to translate more âtalôhkana with the additional purpose of helping preserve this ancient heritage of ours. This commentary, however, acknowledges that some explanation may be necessary for some to make sense of the traditional storytelling format and its characters, both of which were as familiar to our elders when they were children as Cinderella, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, or Mickey Mouse were to us. Let us first turn to some features common to âtalôhkâna.

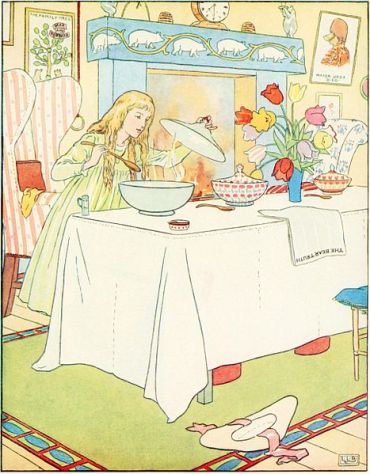

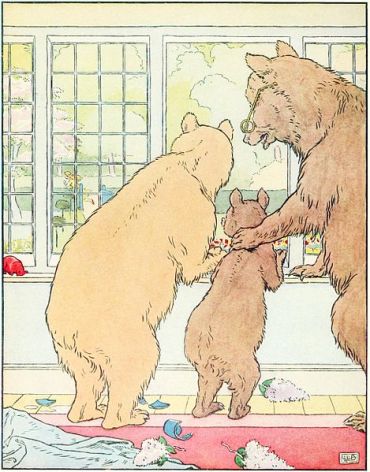

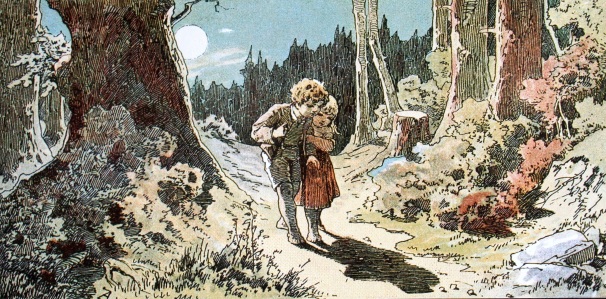

People unfamiliar with âtalôhkâna are often surprised, if not shocked, by the level violence in some of these stories. For those who are familiar with some European fairytales, the stark contrast felt between these and âtalôhkâna is often the result of being unfamiliar with the traditional versions of the stories with which they are familiar. So while these traditional versions often recount violent or morally reprehensible acts, most people are only familiar with censored versions prepared for young children and popularized by large media companies. For instance, most people are unaware of the goriness in the traditional version of Cinderella, such as when one of the step-sisters mutilates her foot to fit the slipper in an attempt to marry the prince. Were it not for her blood drenching the slipper, the prince would surely have been fooled! But the sanitized versions popularized by the media cause our traditional stories to be singled out for being unusually violent. When Diving Duck kills his companion Bear and eats him, is he being any more violent than Hansel & Gretel‘s mother who wants her children killed or the witch who fattens them up and plans to eat them? Sure, the story of Diving Duck wastes no time in presenting this violent sequence, but it isn’t exactly out of the ordinary in its details.

Aside from the unexpected violence, Diving Duck and other âtalôhkâna often involve characters that straddle the boundary dividing people from animals. In the last scene of the Cree version of Diving Duck, the storyteller often alternated between calling the characters persons and birds. In an attempt to avoid any unnecessary confusion, this feature of his narration was omitted from my translation. But his tendency to refer to these characters as both persons and birds is not at all surprising when one considers that the traditional Cree worldview allows for non-humans to be recognized as persons. In addition, the anthropomorphic treatment of otherwise animal characters is a common indicator of the mythological status of stories such as this one.

The story of Diving Duck was told by the late John Blackned from Waskaganish. John, who was born late in the 1800’s, was renowned for his knowledge of âtalôhkâna, among other things. Diving Duck or Kôkîšip (Kôcîšip in the Cree dialect spoken in Waskaganish), was first published by the now defunct Cree Way Project in 1974. It was eventually republished in 2005 and reprinted in 2007 by the Cree School Board. My translation remains faithful to the original, except for a few passages which required stylistic changes or that contained issues that arose when translating from Cree to English. John’s telling of the story can be divided in four scenes as follows:

1) Diving Duck kills and eats Bear

2) Diving Duck hunts caribou

3) Diving Duck flies with geese

4) Diving Duck is invited to a dance as a plot to have him robbed of his two wives

Those who are well versed in traditional stories will notice how the first scene is commonly known throughout Cree country as a story involving a character that westerners call Wîsahkecâhkw, also known as Kwîhkohâkew to easterners. Additionally, The Jesuit Relations from the Saguenay region in the 1600s identify this individual as Meso, which is the name this character continues to be called in certain communities such as Whapmagoostui. Why John calls this character Kôkîšip will probably never be known, but the story remains nearly identical despite the regional nominal differences. To understand the story of Diving Duck, one needs to appreciate the personality of the character otherwise known as Meso, Wîsahkecâhkw, or Kwîhkohâkew.

Meso is a character who epitomizes everything that is basal in human nature. He consistently exceeds the societal bounds we are familiar with, precisely because he exists beyond the bounds of society. As a creature living in a unrestricted and primeval world, Meso repeatedly, and usually unsuccessfully, attempts to satisfy his most powerful desires. His excessive exploits are often comical, but the underlying message is significant; his failures to satisfy his desires, despite his excessiveness, is a reminder of the rationale behind our present societal bounds. Diving Duck is, in fact, this very character and his excessiveness consequently ends in disaster. A few cultural references will now be explained to help clarify the story.

In the first scene, Diving Duck uses the Bear’s poor eyesight to trick him into meeting his death in the sweat lodge. Black Bears actually do have poor eyesight, but the significance of this scene lies in the fact that, until recent times, Cree hunters ritually entered a sweat lodge before embarking on a bear hunt. This was observed until the late 1960s in Mistissini by anthropologists such as Adrian Tanner who took the time to record local practices. The reference to the sweat lodge in the story of Diving Duck would have been understood by all until recent times.

After Diving Duck kills Bear, he tries to satisfy his hunger by eating as much of his body as he can. He becomes so full, however, that he needs to do something to allow his stomach to fit more meat. This is why he asks the trees to squeeze him; presumably his stomach would have room for the rest of Bear’s body once it has been squeezed back to its original size. In another version of this story, animals come and devour what’s left of Bear’s body while the trees hold Diving Duck captive, preventing him from satisfying his hunger.

Near the end of the first scene, Diving Duck calls upon his younger brother Thunderbird to scare the trees into releasing him. The thunderbird, called nimiskiw in Cree, has generally been forgotten in modern times, although the word remains in reference to ‘thunder.’ As such, most people nowadays do not realize that what they commonly translate as ‘thunder’ actually refers to ‘thunderbirds.’ The way we speak of ‘thunder,’ however, is reminiscent of its etymology. For example, when one wishes to say that ‘there is the rumbling of thunder,’ one will say kitowak nimiskiwak, which literally means, ‘the thunderbirds call out.’ Similarly, a ‘thunderstorm’ in Cree will be described as nimiskîskâw, which literally means ‘there are many thunderbirds.’ John Blackned’s story clearly refers to the traditional notion of thunderbirds, which we find clearly described in historical records as well. As a side note, the Cree dialect spoken in the west has lost the word nimiskiw, but has replaced it by piyesiw, which literally means ‘large bird’ in all Cree dialects.

In the fourth scene, Diving Duck’s marriage to two women may seem awkward to some who are unaware of the traditional occurrence of polygyny prior to the introduction of Christianity. Most accounts of polygynous relationships in our traditional stories, however, focus on the jealously they engender. These stories, including the story Diving Duck, usually end in disaster and must have surely dissuaded some men from taking multiple wives.

Again in the fourth scene, Diving Duck capsizes his enemies’ canoe, but prevents them from drowning by forcing them to drink up the whole lake. Fantasy aside, many Cree people traditionally did not know how to swim, despite the fact that we lived most of our lives travelling in and fishing from canoes! Naturally, Diving Duck’s enemies would be expected to drown after they capsized, just like real people.

I must admit that I am at a loss, however, to explain the significance of the caul fat hanging around Diving Duck’s neck during the dance. However, the fact that he was unaware as the other “birds” ate the fat is reminiscent of the âtalôhkân commonly called the Shut Eye Dance in English.

In closing, I hope this brief commentary was interesting and useful. Please feel free to comment if you can clarify any difficult passage from this story that I may have overlooked or if you have any questions that remained unanswered after reading this commentary. I will eventually be translating more âtalôhkâna, all of which will be listed in the link at the top of the page.